Know nothing about how the legislature works?

Schoolhouse Rock's I'm Just a Bill can help you learn the basics!

While in the U.S. Congress only the legislators may introduce bills, ideas for laws may come from a variety of sources:

Legislators: Often the Members of Congress have their own ideas about what laws are needed. For instance Senator Durbin who is often a critic of the banking industry, introduced the Protecting Consumers from Unreasonable Credit Rates Act of 2009, which caps interest rates at 36% including interest and fees.

Citizens: The people themselves often suggest legislation to their congressional representatives. There For instance the citizens in I'm Just a Bill call their representative to make such a suggestion. Some states also permit additional participation of citizens with Referendums and/or Ballot Initiatives.

State Legislators: Calls for national legislation can also come from state legislators. The state and federal legislators often have to create laws that work together to accomplish common goals.

The Executive: President Biden and his predecessors made numerous suggestions for legislation.

Lobbyists: Citizens United (558 US 310) has made unlimited campaign contributions a reality. Often these contributions are accompanied by suggestions for legislation favorable to those who made the contributions.

Only the elected members of Congress can introduce legislation. This simply means that they are officially proposing a change to the law to their fellow congressional members. The folks pictured are Representative for Illinois 12th congressional district, Mike Bost, and the U.S. Senators for Illinois, Tammy Duckworth and Dick Durbin. If you live in Carbondale Illinois, these are the people representing you in the United States congress. If your home is elsewhere, you can find the your congressional representatives here.

elected members of Congress can introduce legislation. This simply means that they are officially proposing a change to the law to their fellow congressional members. The folks pictured are Representative for Illinois 12th congressional district, Mike Bost, and the U.S. Senators for Illinois, Tammy Duckworth and Dick Durbin. If you live in Carbondale Illinois, these are the people representing you in the United States congress. If your home is elsewhere, you can find the your congressional representatives here.

The U.S. Congress has two chambers the House of Representatives and the Senate. Legislation may be introduced in either chamber with the exception of revenue bills which under U.S. Const. Art. 1, § 7 must be introduced in the House.

State legislatures operate much the same way. The biggest exception to this is Nebraska which has a unicameral (one house) legislature. Other differences and similarities between the between state and federal legislatures are beyond the scope of this page. The two people pictured to the left are the state legislators for the SIU School of Law's state districts, Senator for the 59th District, Dale Fowler and Representative for the 118th District Paul Jacobs. You can find your own state legislators here.

State legislatures operate much the same way. The biggest exception to this is Nebraska which has a unicameral (one house) legislature. Other differences and similarities between the between state and federal legislatures are beyond the scope of this page. The two people pictured to the left are the state legislators for the SIU School of Law's state districts, Senator for the 59th District, Dale Fowler and Representative for the 118th District Paul Jacobs. You can find your own state legislators here.

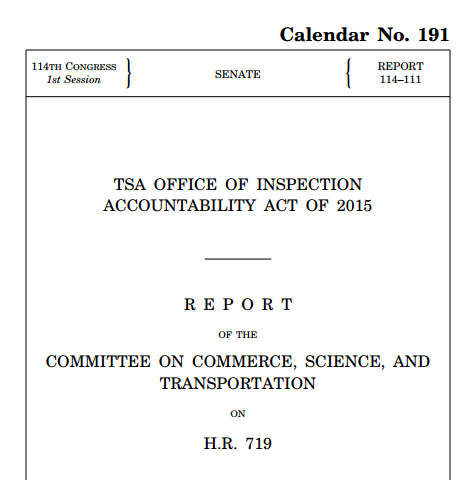

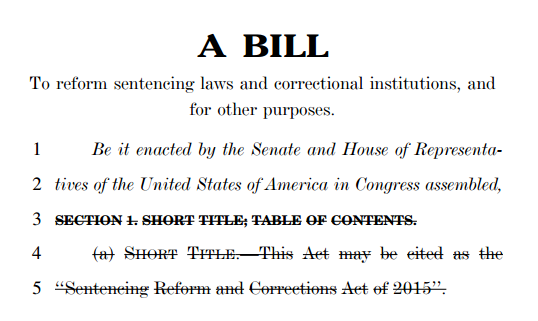

The document produced by introduction to either chamber is the bill. Once a bill is introduced it is assigned a bill number. In the U.S. Congress bills are numbered in a standard way:

(Bluebook §13.2)

Title: the title usually refers to the "Short Title" section from a bill

Bill Number: Bills are numbered sequentially. In this example the "S." indicates this bill introduced in the U.S. Senate. The number "1140" indicates this was the 1140th bill introduced in the Senate. Bills introduced in the House of Representatives are prefaced with "H.R."

NOTE: People new to legislative history research sometimes confuse different legislative history documents due to the similarity in citations. A comparison chart can be found in §13.1 of the Bluebook.

Congress: This refers to the Congress which considered the bill. Here, the 114th Congress.

Year: Yep, the year this version of the bill was written.

When introducing a bill, the primary sponsor of the bill might make a Statement of Introduction which can summarize the bill or discuss why the legislation is being proposed. These statements are published in the Congressional Record along with the list of bills introduced that day.

The bill number is usually the key to finding other legislative history documents.

Once bills are introduced to congress they are then assigned to one or more committees based on  the subject matter of the bill. In the U.S. Congress, assignment of a bill to a committee is officially made by the leadership in each chamber, the Speaker in the House or the Vice President or the President Pro-Tem in the Senate.

the subject matter of the bill. In the U.S. Congress, assignment of a bill to a committee is officially made by the leadership in each chamber, the Speaker in the House or the Vice President or the President Pro-Tem in the Senate.

In practice, each chamber has a Parliamentarian who makes the actual decision based on standing rules and the precedent of past committee referral decisions. The referral decions are not partisan in nature. The current parliamentarians are Jason Smith in the House and Elizabeth MacDonough in the Senate. Usually, bills are assigned to one committee though multiple committee assignments are not uncommon in either chamber. If assigned to multiple committees, one committee is usually designated as the primary.

Once a bill is assigned to a committee the committee can then assign the bill to a subcommittee. Generally, both committees and subcommittees have the authority to consider and report on bills and have many actions they could take. The current congress has over 200 committees, subcomittees, and joint committees. Here are the main ways they might treat a bill:

Do Nothing: A committee could simply ignore a bill which will prevent further consideration of the legislation. This is also known as "Dying in Committee."

Request the Congressional Research Service (CRS) investigate: The CRS is a branch of he Library of Congress which conducts research exclusively for Members of Congress. The findings of CRS investigations are confidential prior to 2018 it wasat the discretion of the requesting legislator whether to disclose the information to the public. Since 2018 CRS reports have been made available to the public. The document produced is called a CRS Report. (Bluebook §13.4(d))

Hold a Hearing: Congress will often hold public hearings to investigate issues surrounding important legislation. Hearing documents include written and spoken statements of witnesses as well as transcripts of committee member's questioning of witnesses. Witnesses at congressional hearings can include high ranking members of the executive branch, experts on the subject in question, ordinary citizens who have personal experience with the issues, or even celebrities, such as Stephen Colbert. Witnesses can either be voluntary or subpoenaed. The document produced is called a Congressional Hearing. (Bluebook §13.3)

Issue a Report: If the committee or subcommittee decides to report favorably on the bill it will issue a report. While opinions vary, many scholars consider Committee Reports the gold standard for determining legislative intent because they include the committee's reasoning for suggesting the bill be passed by Congress. The document produced is called a Committee Report.(Bluebook §13.4(a))

Amend the Bill: Committees will sometimes change the text of the bill before suggesting it be passed. S. 2123 is an example of a marked-up bill.

Issue Committee Print: Committee Prints (Bluebook §13.4(c)) are another sort of legislative history document. They are distributed for the internal use of committees and subcomittees. They could be drafts of reports or bills, directories, statistical materials, investigative reports, historical reports, situational studies, confidential staff reports, hearings, or legislative analyses. Committee prints are not necessarily related to specific legislation and only the Senate has a consistent numbering system for committee prints.

State Legislative Committees: Committees in state legislatures will usually operate in a similar way and produce similar documents (committee reports, etc.) . Committee reports in some states may also be limited to a simple response, i.e. "pass" "do not pass". Most federal legislative history documents are available for through various commercial and free government online sources. The availability of state legislative history varies wildly from state to state. We'll cover this in greater detail in a another section.

Once a committee or subcommittee reports favorably on a bill, it returns to the chamber where it originated. From here several things can happen:

Debate: Debate about the bill can ensue. The floor proceedings of both chambers are recorded and transcribed in the Congressional Record. (Bluebook §13.5) Any floor debates about the bill and statements made about the bill from the floor can be found there.

Floor Amendments: Sometimes, rather than ending in fistfights, floor debates result in the bill being amended. When this happens we again end up with a Marked-Up Bill.

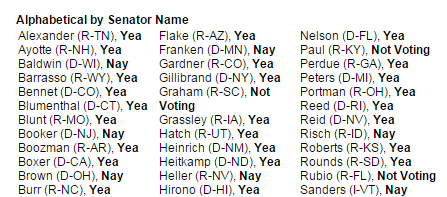

Vote: Most bills that get this far end up with a vote. Most votes are simply a Yea or Nay affair. In some instances a member of congress will request that the other members votes be recorded. This is called a Roll Call Vote.

If the bill passes in it's originating chamber, it is called an Engrossed Bill. These are sent to the other chamber and the whole thing starts again! Oh Yeah!

When the exact same version of a bill passes both chambers, it is called an Enrolled Bill. Such bills are sent to the executive for their consideration.

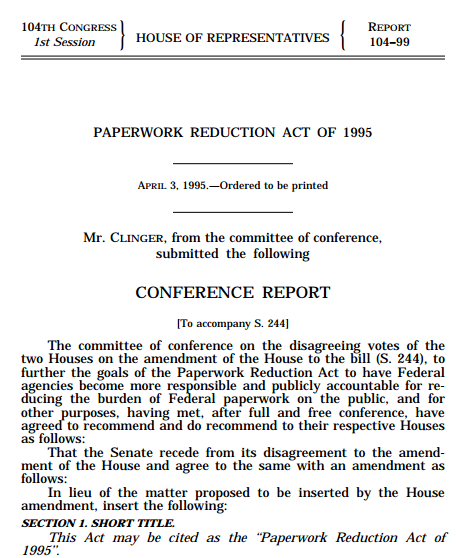

However, when the House and Senate pass different versions of the same bill, the differences must be resolved before the legislation can be offered for executive consideration. A conference committee is formed to hammer out the differences between the House and Senate versions of a bill.

The conference committee generally consists of the leaders of the committees which considered the bill being discussed and senior members of congress. Should the legislators be able to resolve the differences in the bill it will issue a Conference Report which accompanies yet another Marked-up Bill. It is important to note that conference reports are designated as a House or Senate Report and do not have their own special designation though such documents will self-identify as conference reports.

The conference committee generally consists of the leaders of the committees which considered the bill being discussed and senior members of congress. Should the legislators be able to resolve the differences in the bill it will issue a Conference Report which accompanies yet another Marked-up Bill. It is important to note that conference reports are designated as a House or Senate Report and do not have their own special designation though such documents will self-identify as conference reports.

Some experts consider the Conference Report to be the gold standard of legislative history documents because it reflects the bargaining between the house and Senate necessary to pass the legislation.

This bill is then submitted to both the House and Senate which may vote the bill up or down but my not make further amendments. If this amended bill passes both chambers, it then becomes an Enrolled Bill and is submitted to the executive.

Once an Enrolled Bill arrives, the President has several ways to dispose of the bill:

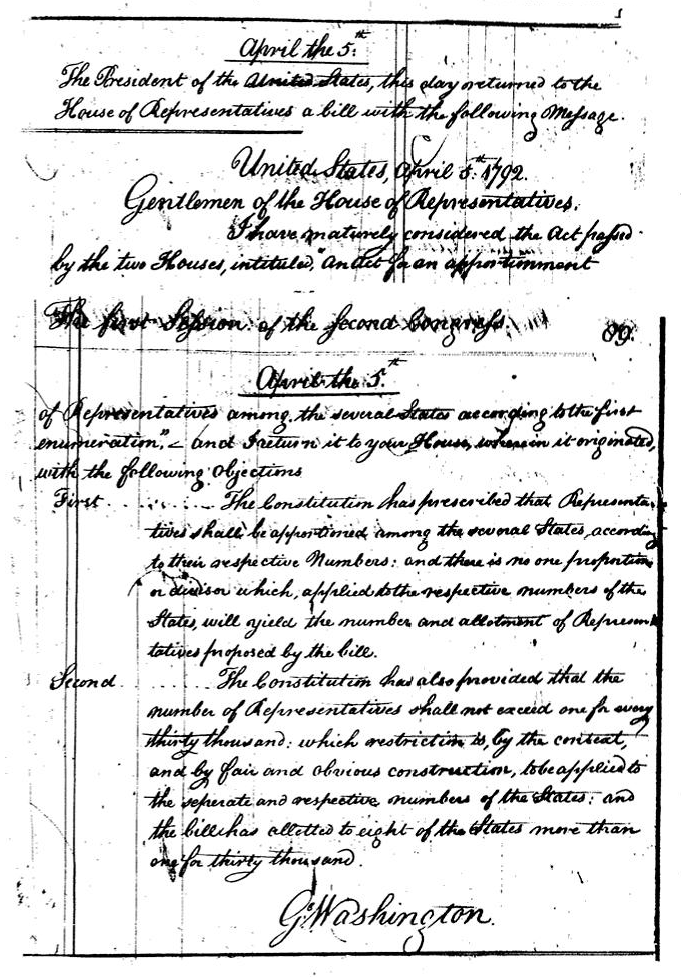

The President could veto the bill. To veto a bill simply means the President refuses to sign the bill and it doesn't become law. When a President does this, he or she may also write a message to congress explaining why the bill was vetoed. To the right is the first usage of such a Veto Message (Bluebook, 21st ed., p.238). Here, George Washington informed Congress that he vetoed an apportionment bill which violated the Constitution on April 5, 1792.

If a bill has sufficient support in Congress a presidential veto can be overridden. To override, a bill would need the votes of two thirds of the members in both the House and Senate. This level of support is rare, with Congress overriding less than ten percent of presidential vetoes.

The President could also dispose of enrolled bills by doing nothing, which could have two different results. If the President is in possession of the enrolled bill for ten days and does not veto the bill, the bill becomes law without the President's signature. However, if within those ten days Congress adjourns, the bill does not become law. This is known as a Pocket Veto.

Finally, the President could simply sign the bill. In this case, the bill becomes law and goes on to the statutory publication process. Sometimes presidents will issue a Signing Statement (Bluebook, 21st ed., p.238) at the time they sign the bill which might reflect their understanding of the legislation or influence the way in which executive agencies interpret the law or implement it through.

Federal statutes are published in three stages. State legislatures will vary in this process, some collapsing the first two steps into one.

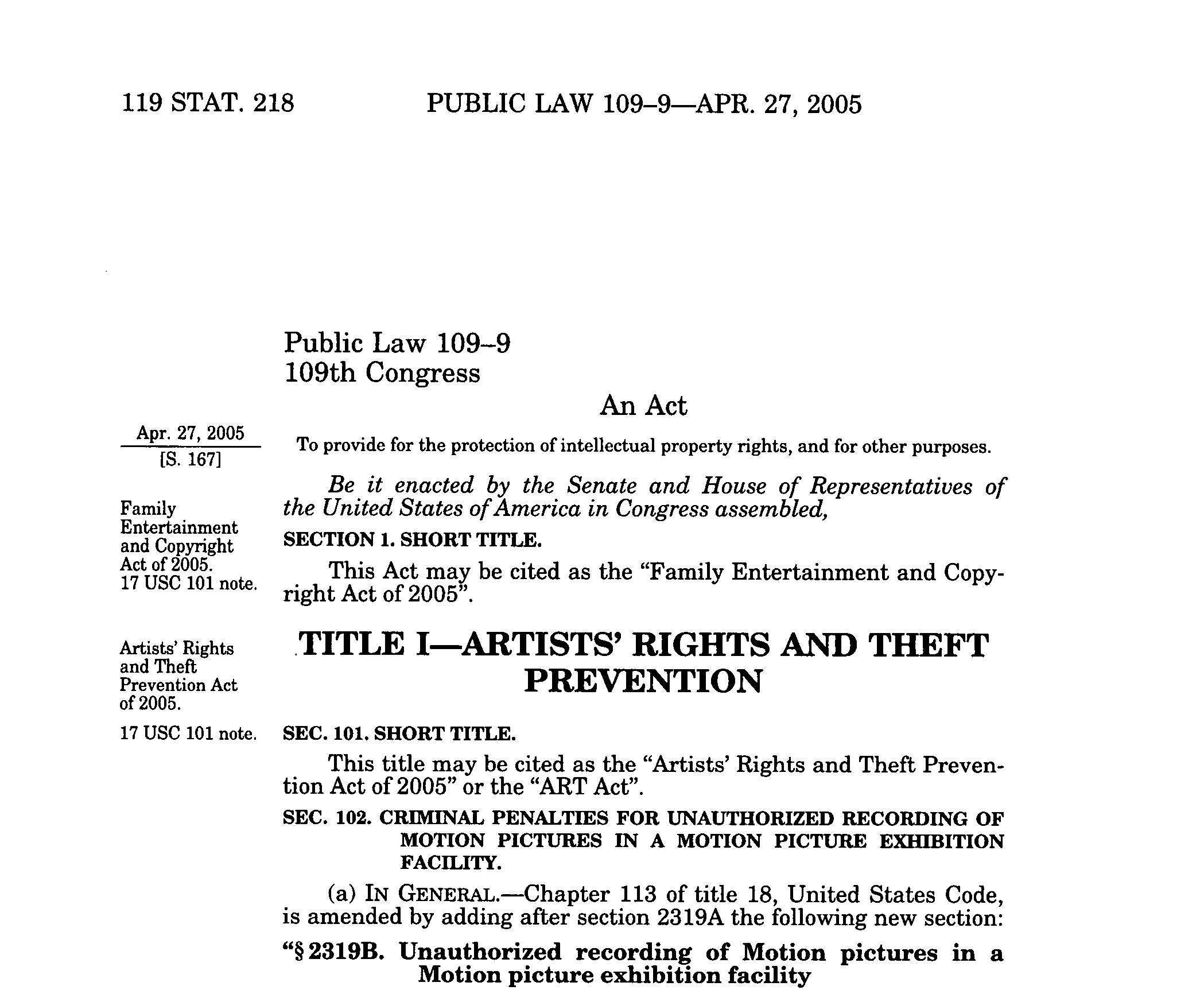

First, Slip Laws (Bluebook §12.4)) are published. A slip law, such Public Law 112-102 is a publication consisting of one statute. Slip laws are published as legal evidence of the passage of the statute. This example is from the SIU Law Library print collection. At the federal level, this is the first step in publishing a statute. Citation of slip laws follows a format consisting of the designation "Public Law" and two numbers, the first number is the number of the congress which passed the law and the second is the ordinal number. Many states have stopped publishing slip laws in favor of promulgating such information online, usually through a state legislature website. A single slip law will vary considerably in length. Some do not fill a single sheet of paper and others are hundreds of pages. It is also important to note that a single Public Law may be codified in hundreds of different sections of U.S. Code and may be in several different titles.

Session Laws (Bluebook §12.4)) are bound collections of slip laws. The U.S. Congress's session law book is titled Statutes at Large. Currently one new volume of Statutes at Large is printed each year. Note that the format is very consistent with slip laws. Slip laws currently include volume and page information for the Statutes at Large volume in which they are to be printed and both include usually include information about where specific sections of the statute will be codified. Statutes at Large is the official source of statutory law in the United States (i.e. if U.S. Code differs from Statutes at Large, Statutes at Large prevails). Many state legislatures do not make a distinction between slip and session laws. States may have also ceased printing session laws in favor of promulgating such information online, usually through a state legislature website.

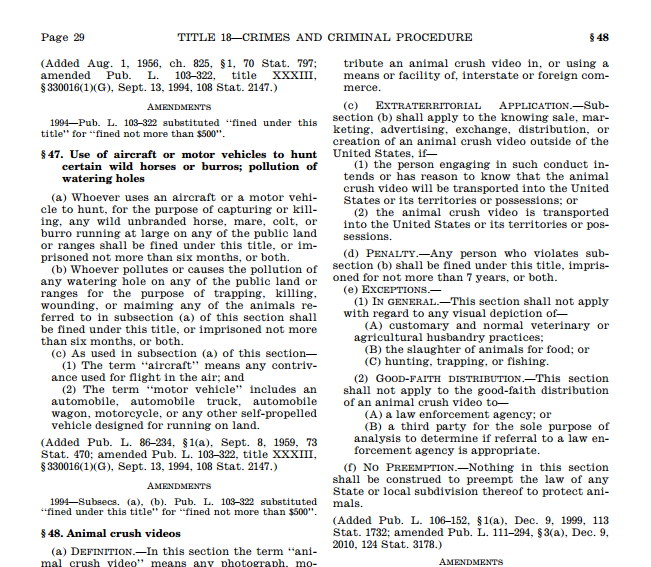

Whereas session laws are published chronologically, Statutory Codes (Bluebook §12.3)) are arranged the by subject area. Codes are also supposed to represent the current statutory law of the jurisdictions they cover. The United States Code is the official statutory code of the United States. There are currently 54 numbered "Titles" in U.S. Code representing the top level of the subject organization. The example here is from Title 18, which is concerned with Crimes and Criminal Procedure. . The section listed, 18 U.S.C. §47, prohibits the hunting of wild horses or burros using aircraft or motor vehicles or the pollution of watering holes. United States Code is kept current through the efforts of the Office of the Law Revision Counsel.

State legislatures also codify their statues. Some jurisdictions follow an organizational pattern similar to that of the Federal Government. Others, like California and New York have separate codes for different legal subjects.